Frequently Asked Questions

Why don't private sector employees have Garrity Rights?

The answer lies in the applicability of the rights contained in the United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights. The Constitution protects citizens from the actions of government, not the actions of private employers.

When a public employee is being questioned by their employer, they are being questioned by the government. Therefore, the Fifth Amendment applies to that interrogation, if it is related to potentially criminal conduct.

The Fourteenth Amendment makes this applicable not just to the federal government, but to state and local governments as well.

On the other hand, the Constitution does not protect citizens from the actions of private entities, such as private employers. If you work for a manufacturing company or a restaurant, for example, and your employer questions you about a potentially criminal matter, this is not a case of the government questioning you. Therefore, there is no protection from being compelled to incriminate yourself.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Aren't these "special rights" for public employees?

Not at all. Regardless of whether one is a public employee or a private sector employee, everyone has the right not to be compelled to incriminate themselves when questioned by the government.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

What's the difference between Garrity Rights and Weingarten Rights? And Loudermill Rights?

These are entirely separate and distinct rights. People confuse them because they often come into play at the same time.

Garrity Rights apply to the right of a public employee not to be compelled to incriminate themselves by their employer. These rights are based on the 1967 United States Supreme Court decision Garrity v. New Jersey. Garrity Rights apply only to public employees, because they are employed by the government itself.

Weingarten Rights apply to the right of a unionized employee to request union representation for any investigatory interview conducted by their employer, in which the employee has the reasonable belief that the discussion could lead to disciplinary action. These rights are based on the 1975 United States Supreme Court decision NLRB v. J. Weingarten Inc. The Weingarten decision itself applies only to private sector employees, but the federal government and many states have extended similar rights to public employees via legislation, court decision, and/or rulings by state labor boards. In some cases, unionized public employees have enshrined Weingarten Rights into their collective bargaining agreements.

Loudermill Rights require due process before a public employee can be dismissed from their job. These rights are based on the 1985 United States Supreme Court decision Cleveland Board of Education v. Loudermill. Generally, these rights require a public employer to offer to have a "pre-termination" meeting with the affected employee; at this meeting, the employer presents their grounds for termination, and the employee is given the opportunity to respond.

Like Garrity Rights, these rights only apply to public employees because they are employed by the government itself, and the Constitution only applies to actions taken by the government. A private sector employee - for example, a manufacturing worker - possesses only Weingarten Rights, and only if s/he is in a unionized workplace.

A public sector employee possesses Garrity Rights and Loudermill Rights because their employer is the government, regardless of whether he/she works in a unionized workplace. The same public sector employee may possess rights similar or identical to Weingarten Rights, provided they work in a unionized workplace.

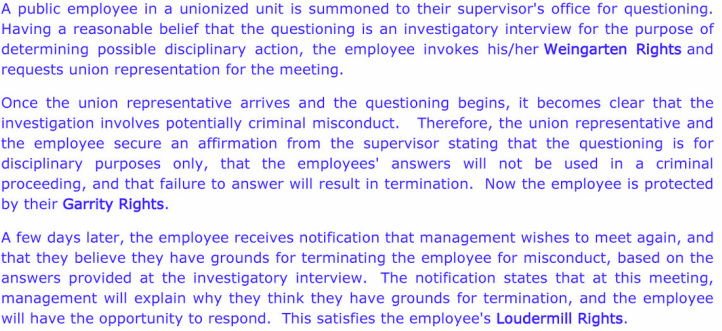

Below is a scenario in which all three sets of rights could coexist. This demonstrates that public employees and their representatives must have a clear understanding of these three sets of rights - not only an understanding of how they are separate and distinct, but also an understanding of how their functions can overlap.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Can I be forced to waive my Garrity Rights?

No. The United States Supreme Court ruled in 1968's Gardner v. Broderick that public employers cannot use a threat of termination to force employees to waive their constitutional rights.

However, some employers might attempt to convince or persuade an employee to cooperate by using leverage short of termination. By using penalties such as unwelcome schedule changes or assignment to unattractive duties, employers might try to bring about cooperation without making threats of severe discipline or termination. Employees who give statements under such circumstances are very unlikely to be protected by Garrity, as courts would find that their cooperation was voluntary and not compelled.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Do Garrity Rights apply if I'm investigated by an outside agency?

If you are a public employee and are investigated by an outside agency, Garrity Rights can still apply if you are clearly subject to severe disciplinary action or termination if you refuse to answer the outside agency's questions. Typically, your own agency will order you to cooperate with the outside investigator; if this order is made, and the penalty for refusing to comply is made clear and is severe (generally termination), then Garrity Rights apply.

Employees should be careful they are not assuming the nature and severity of the penalty; if your own employing agency does not make clear statements or have clear policies and procedures that require severe discipline or termination for refusal to participate in such an investigation, you are probably not protected.

A recent example is U.S. v. Lamb, a 2010 West Virginia case in which a firefighter was summoned by his captain to speak to federal law enforcement agents. A court determined that the employee's Garrity Rights had not been violated because the captain had not ordered the employee to answer the federal agents' questions, and the employee had not been threatened with termination for refusing to cooperate.

Be sure you are not relying solely upon the statements of the outside investigator; they do not have the power to discipline or terminate you. A court would probably rule that compulsion cannot be caused by threats made by an outside party.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

What is "compulsion?"

The Fifth Amendment states that the government cannot compel a person to incriminate themselves; Garrity brings this into the employment relationship, affirming that a governmental employer cannot compel their employees to incriminate themselves. The key to defining "compulsion" revolves primarily around one question: what is the penalty for refusing to answer questions? In general, the courts have found that if a public employer threatens an employee with severe administrative sanctions - usually termination - for refusal to answer questions, then the employee's statements are considered compelled and therefore unusable against the employee in any future criminal proceeding.

It is important to note, however, that the precise definition of "compulsion" has varied in court decisions across the country. The answer to the question, "What is compulsion?" can depend on where you live. Most courts, including the United States Supreme Court, have taken a broad view of "compulsion." Courts have ruled a variety of threatened penalties as sufficient to bring about "compulsion," including disbarment, suspension, demotion, and in general, any "substantial economic penalty."

However, some courts have held that only a threat of termination is sufficient to bring about compulsion, and further, that this threat must be made very clearly. The U.S. District Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, which covers the states of Maine, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire, has stated that only termination can cause compulsion, and that this threat of termination must be explicit in order for the employee to be protected by Garrity Rights (see U.S. v. Indorato). Other jurisdictions potentially subject to this narrow view include Illinois (People v. Bynum, 1987), Florida (United States v. Camacho, 1990), New Jersey (New Jersey v. Lacaillade, 1993), Idaho (State v. Connor, 1993), Minnesota (United States v. Najarian, 1996), Colorado (People v. Sapp, 1997, and Hopp & Flesch, LLC v. Backstreet, 2005) and Wisconsin (Wisconsin v. Brockdorf, 2006).

To have a complete understanding of this question, you must be familiar with the case law in your area.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Does management have to advise an employee of their rights?

In federal employment and in states under the jurisdiction of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit (Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin), the employer has the affirmative duty to inform the employee of their Garrity Rights. Public employers in the state of California must also advise employees of their rights.

The requirement in federal employment stems from the 1973 case Kalkines v. United States. This is why, in federal employment, the documents advising employees of their rights are routinely called "Kalkines Warnings." The requirement in the Seventh Circuit stems most notably from Confederation of Police v. Conlisk and Atwell v. Lisle Park District, leading some to give this doctrine the name "Conlisk-Atwell."

It can also be argued that a similar approach was embraced by the Second Circuit (Connecticut, New York, Vermont) in Uniformed Sanitation II, in which the court said that public employees "subject themselves to dismissal if they refuse to account for their performance of their public trust, after proper proceedings, which do not involve an attempt to coerce them to relinquish their constitutional rights" (625). The phrase "after proper proceedings" has been interpreted by some to mean an advisement of the employee's rights.

Whether based on Kalkines, Conlisk-Atwell, or Uniformed Sanitation II, these advisements usually take the form of a document advising the employee of their rights.

In California, the duty to advise public employees of their rights results from the 1985 case Lybarger v. City of Los Angeles, in which the court found that the state's Public Safety Officers Procedural Bill of Rights required such an advisement if the employee could potentially be charged with a criminal offense.

Outside of federal employment, the states of the Seventh Circuit (and perhaps the states of the Second Circuit), and the state of California, public employers have no such obligation.

In other jurisdictions, many public employers have voluntarily adopted the practice of administering an advisement document prior to questioning.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Are Garrity Rights automatically "triggered," or must they be granted/extended?

I am of the opinion that Garrity Rights can be triggered by the actions/statements of the public employer, regardless of whether any prior affirmation or discussion of those rights ever takes place.

As soon as the employer orders the employee to answer questions and threatens them with severe discipline (usually termination) for refusing to answer, Garrity Rights, in my opinion, automatically apply. The order to answer and the threat of termination trigger use/derivative use immunity for the statements the employee makes. At no time does the employer have to say "I am activating your Garrity Rights." Similarly, the triggering of Garrity Rights does not require the employee to "invoke" them. Once the employee is ordered to answer and threatened with termination for refusing to do so, use/derivative use immunity applies to their subsequent statements during that interview.

In Uniformed Sanitation II, the Second Circuit said, in reference to the original Garrity case, "the very act of the attorney general in telling the witness that he would be subject to removal if he refused to answer was held to have conferred such immunity" (626).

In a footnote to Wiley v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, the Fourth Circuit stated, “Garrity immunity is self-executing." The court did note, however, that "In an appropriate case, it might be necessary to inform an employee about its nature and scope” (778). Other courts which have held that Garrity Rights can be "triggered" include the Eleventh Circuit in Hester v. City of Milledgeville and the Fifth Circuit in Gulden v. McCorkle.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Can Garrity Rights be "invoked" by the employee?

Sort of, but not really. What some may view as an "invocation" of one's rights is really just a statement of rights - rights that exist whether or not the employee "invokes" them. Garrity protection depends on whether they are ordered to answer questions, whether the answers to those questions could incriminate the employee, and whether there is a severe penalty - usually termination - for refusing to answer questions.

What the employee can invoke is their Fifth Amendment right not to give a statement. However, this right disappears once Garrity is triggered. Once the employee has been threatened with severe discipline or termination for refusal to answer, they are protected by Garrity and its use/derivative use immunity, and can no longer stand on the Fifth Amendment. See Uniformed Sanitation II.

In one possible scenario, an employee is called in for questioning, and is told they are required to answer questions. They are also told that if they refuse, they will be terminated. The employee emphatically announces, "I am invoking my Garrity Rights." What does this mean? Their invocation does not trigger their protection - the actions of the employer triggered Garrity protection before the employee said a word. Does their invocation now entitle them not to answer questions? Absolutely not. As previously stated, once use/derivative use immunity has been activated, the employee can no longer refuse to answer questions. So it is difficult to ascertain what the employee's invocation of their rights actually accomplishes. However, it must be acknowledged that an employee in an investigatory situation should endeavor to "cover all the bases" and make sure all parties are aware of the rights and obligations in place at the time; thus an invocation/affirmation of these rights certainly does no harm.

In an alternate scenario, the employee is called in for questioning, and upon entering the room, emphatically announces, "I am invoking my Garrity Rights." What does this mean? They have not been given any directives, nor have they been threatened with any penalty, real or implied. No compulsion has occurred yet. Therefore, Garrity Rights have not yet been triggered, notwithstanding the employee's invocation. Again, in a legal sense, the employee invocation accomplishes little; but it does no harm, as long as the employee fully understands it.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

What is use/derivative use immunity?

When people are given complete immunity from prosecution for a particular crime, it is known as "transactional" immunity.

In Garrity Rights cases, the immunity is not complete "transactional" immunity. In 1972's Kastigar v. United States, the Supreme Court held that immunity for compelled statements only applies to the use of the statements themselves, and to any evidence gained as a result of the protected statements. This is known as "use and derivative use" immunity, in which "use" is the use of the protected statements, and "derivative use" pertains to any evidence gained as a result of the protected statements. It is also known as "use plus fruits" immunity.

This means that the person in question can still be prosecuted for the offense under investigation, as long as the prosecution relies solely on evidence other than the protected statements and their fruits.

The result is that in many cases, what is known as a "Kastigar Hearing" takes place, in which the prosecution must demonstrate that its case rests solely on evidence other than the protected statements and their fruits.

Recently, this was significant in relation to the Nisour Square incident of September 16, 2007. On that day, Blackwater military contractors in Iraq killed 17 civilians in Baghdad's Nisour Square. In December 2008, the United States Department of Justice brought criminal charges against five of the contractors who had been involved, but the charges were dismissed in late 2009 because the prosecution had utilized evidence that was gained as a result of compelled statements.

It should be noted that full transactional immunity for compelled statements does apply in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as a result of the 1988 state supreme court decision in Carney v. City of Springfield.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

If I have Garrity protection, can I still take the Fifth and refuse to answer questions?

No. In "Uniformed Sanitation II," the court determined that once employees are protected by Garrity - meaning, their statements are protected by "use/derivative use" immunity - they are no longer able to refuse to answer questions. This is because once use/derivative use immunity is assured, the employee is no longer being required to give self-incriminating statements.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

I made statements after being told that if I refused to answer questions, I would face "discipline up to and including termination." Are my statements protected?

You are on potentially shaky ground, depending on where you live. In the states of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit (Maine, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire), the courts would likely find that your statements were voluntary because, while termination was a possibility, other less-severe sanctions were possibilities as well. See, for example, United States v. Indorato, Commonwealth v. Harvey, Singer v. Maine, Dwan v. City of Boston, and New Hampshire v. Litvin.

A number of other jurisdictions potentially subject to this narrow view include Illinois (People v. Bynum, 1987), Florida (United States v. Camacho, 1990), New Jersey (New Jersey v. Lacaillade, 1993), Idaho (State v. Connor, 1993), Minnesota (United States v. Najarian, 1996), Colorado (People v. Sapp, 1997, and Hopp & Flesch, LLC v. Backstreet, 2005) and Wisconsin (Wisconsin v. Brockdorf, 2006).

While many courts would find "discipline up to and including termination" coercive enough to trigger Garrity protection, it is also not hard to imagine other courts finding that coercion has not occurred if dismissal was possible but not definite. Obviously, then, the only way to be completely sure your statements are protected is to ensure that you are unequivocally subject to termination for refusal to answer. Otherwise, you gamble with the possibility that a court will deem your statements voluntary.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

What happened to Chief Garrity after Garrity v. New Jersey was decided?

Edward Garrity returned to his job as police chief of the township of Bellmawr, New Jersey. In 1969, just two years after the Garrity decision by the Supreme Court, he received the J. Edgar Hoover Award for Law Enforcement in New Jersey.

He retired from the Bellmawr police department in 1978, after serving as chief of police since 1951. Upon his retirement, he joined the Camden County Prosecutor's Office. He died in 2000.

It is also interesting to note that his father, James Garrity, was Bellmawr's chief of police from 1930-1949. So with just a two-year gap from 1949-1951, a member of the Garrity family was the township's police chief from 1930 to 1978.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Does Garrity protect false statements?

No. If an employee makes false statements under Garrity protection, they can be prosecuted for making false statements, and their statements can be used against them in that prosecution.

A number of courts have ruled that Garrity does not protect false statements. See McKinley v. City of Mansfield (6th Cir. 2005), U.S. v. Veal (11th Cir. 1998), FOP Lodge No. 5 v. City of Philadelphia (3rd Cir. 1988), U.S. v. Devitt (7th Cir. 1974), and U.S. ex. rel. Annunziato v. Deegan (2nd Cir. 1971).

The United States Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled that the Fifth Amendment does not shield perjured or false statements. See U.S. v. Wong (1977), U.S. v. Mandjuano (1976), and U.S. v. Knox (1969).

______________________________________________________________________________________

Does Garrity apply to drug tests, breathalyzer tests, etc?

No. Remember that Garrity Rights relate to the right not to be compelled to incriminate oneself. Courts have consistently found that this Fifth Amendment right applies only to statements, not to physical evidence. In Schmerber v. California, the United States Supreme Court stated that "the privilege is a bar against compelling 'communications' or 'testimony,' but that compulsion which makes a suspect or accused the source of 'real or physical evidence' does not violate it" (764). This doctrine extends as far back as 1910's Holt v. United States and even 1886's Boyd v. United States.

More recently, in the 2008 case Illinois v. Carey, a police officer who had been arrested for DUI argued that his breathalyzer results should be suppressed because he had been threatened with termination if he refused to take the test. The Illinois appellate court disagreed, saying that "it is well settled that the Fifth Amendment applies only to testimonial or communicative evidence and that it does not apply to physical evidence" (1139).

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

My question is not listed here. What can I do?

Feel free to contact me - I'll do my best to answer your question, or at least point you in the right direction.

No. The United States Supreme Court ruled in 1968's Gardner v. Broderick that public employers cannot use a threat of termination to force employees to waive their constitutional rights.

However, some employers might attempt to convince or persuade an employee to cooperate by using leverage short of termination. By using penalties such as unwelcome schedule changes or assignment to unattractive duties, employers might try to bring about cooperation without making threats of severe discipline or termination. Employees who give statements under such circumstances are very unlikely to be protected by Garrity, as courts would find that their cooperation was voluntary and not compelled.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Do Garrity Rights apply if I'm investigated by an outside agency?

If you are a public employee and are investigated by an outside agency, Garrity Rights can still apply if you are clearly subject to severe disciplinary action or termination if you refuse to answer the outside agency's questions. Typically, your own agency will order you to cooperate with the outside investigator; if this order is made, and the penalty for refusing to comply is made clear and is severe (generally termination), then Garrity Rights apply.

Employees should be careful they are not assuming the nature and severity of the penalty; if your own employing agency does not make clear statements or have clear policies and procedures that require severe discipline or termination for refusal to participate in such an investigation, you are probably not protected.

A recent example is U.S. v. Lamb, a 2010 West Virginia case in which a firefighter was summoned by his captain to speak to federal law enforcement agents. A court determined that the employee's Garrity Rights had not been violated because the captain had not ordered the employee to answer the federal agents' questions, and the employee had not been threatened with termination for refusing to cooperate.

Be sure you are not relying solely upon the statements of the outside investigator; they do not have the power to discipline or terminate you. A court would probably rule that compulsion cannot be caused by threats made by an outside party.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

What is "compulsion?"

The Fifth Amendment states that the government cannot compel a person to incriminate themselves; Garrity brings this into the employment relationship, affirming that a governmental employer cannot compel their employees to incriminate themselves. The key to defining "compulsion" revolves primarily around one question: what is the penalty for refusing to answer questions? In general, the courts have found that if a public employer threatens an employee with severe administrative sanctions - usually termination - for refusal to answer questions, then the employee's statements are considered compelled and therefore unusable against the employee in any future criminal proceeding.

It is important to note, however, that the precise definition of "compulsion" has varied in court decisions across the country. The answer to the question, "What is compulsion?" can depend on where you live. Most courts, including the United States Supreme Court, have taken a broad view of "compulsion." Courts have ruled a variety of threatened penalties as sufficient to bring about "compulsion," including disbarment, suspension, demotion, and in general, any "substantial economic penalty."

However, some courts have held that only a threat of termination is sufficient to bring about compulsion, and further, that this threat must be made very clearly. The U.S. District Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, which covers the states of Maine, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire, has stated that only termination can cause compulsion, and that this threat of termination must be explicit in order for the employee to be protected by Garrity Rights (see U.S. v. Indorato). Other jurisdictions potentially subject to this narrow view include Illinois (People v. Bynum, 1987), Florida (United States v. Camacho, 1990), New Jersey (New Jersey v. Lacaillade, 1993), Idaho (State v. Connor, 1993), Minnesota (United States v. Najarian, 1996), Colorado (People v. Sapp, 1997, and Hopp & Flesch, LLC v. Backstreet, 2005) and Wisconsin (Wisconsin v. Brockdorf, 2006).

To have a complete understanding of this question, you must be familiar with the case law in your area.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Does management have to advise an employee of their rights?

In federal employment and in states under the jurisdiction of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit (Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin), the employer has the affirmative duty to inform the employee of their Garrity Rights. Public employers in the state of California must also advise employees of their rights.

The requirement in federal employment stems from the 1973 case Kalkines v. United States. This is why, in federal employment, the documents advising employees of their rights are routinely called "Kalkines Warnings." The requirement in the Seventh Circuit stems most notably from Confederation of Police v. Conlisk and Atwell v. Lisle Park District, leading some to give this doctrine the name "Conlisk-Atwell."

It can also be argued that a similar approach was embraced by the Second Circuit (Connecticut, New York, Vermont) in Uniformed Sanitation II, in which the court said that public employees "subject themselves to dismissal if they refuse to account for their performance of their public trust, after proper proceedings, which do not involve an attempt to coerce them to relinquish their constitutional rights" (625). The phrase "after proper proceedings" has been interpreted by some to mean an advisement of the employee's rights.

Whether based on Kalkines, Conlisk-Atwell, or Uniformed Sanitation II, these advisements usually take the form of a document advising the employee of their rights.

In California, the duty to advise public employees of their rights results from the 1985 case Lybarger v. City of Los Angeles, in which the court found that the state's Public Safety Officers Procedural Bill of Rights required such an advisement if the employee could potentially be charged with a criminal offense.

Outside of federal employment, the states of the Seventh Circuit (and perhaps the states of the Second Circuit), and the state of California, public employers have no such obligation.

In other jurisdictions, many public employers have voluntarily adopted the practice of administering an advisement document prior to questioning.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Are Garrity Rights automatically "triggered," or must they be granted/extended?

I am of the opinion that Garrity Rights can be triggered by the actions/statements of the public employer, regardless of whether any prior affirmation or discussion of those rights ever takes place.

As soon as the employer orders the employee to answer questions and threatens them with severe discipline (usually termination) for refusing to answer, Garrity Rights, in my opinion, automatically apply. The order to answer and the threat of termination trigger use/derivative use immunity for the statements the employee makes. At no time does the employer have to say "I am activating your Garrity Rights." Similarly, the triggering of Garrity Rights does not require the employee to "invoke" them. Once the employee is ordered to answer and threatened with termination for refusing to do so, use/derivative use immunity applies to their subsequent statements during that interview.

In Uniformed Sanitation II, the Second Circuit said, in reference to the original Garrity case, "the very act of the attorney general in telling the witness that he would be subject to removal if he refused to answer was held to have conferred such immunity" (626).

In a footnote to Wiley v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, the Fourth Circuit stated, “Garrity immunity is self-executing." The court did note, however, that "In an appropriate case, it might be necessary to inform an employee about its nature and scope” (778). Other courts which have held that Garrity Rights can be "triggered" include the Eleventh Circuit in Hester v. City of Milledgeville and the Fifth Circuit in Gulden v. McCorkle.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Can Garrity Rights be "invoked" by the employee?

Sort of, but not really. What some may view as an "invocation" of one's rights is really just a statement of rights - rights that exist whether or not the employee "invokes" them. Garrity protection depends on whether they are ordered to answer questions, whether the answers to those questions could incriminate the employee, and whether there is a severe penalty - usually termination - for refusing to answer questions.

What the employee can invoke is their Fifth Amendment right not to give a statement. However, this right disappears once Garrity is triggered. Once the employee has been threatened with severe discipline or termination for refusal to answer, they are protected by Garrity and its use/derivative use immunity, and can no longer stand on the Fifth Amendment. See Uniformed Sanitation II.

In one possible scenario, an employee is called in for questioning, and is told they are required to answer questions. They are also told that if they refuse, they will be terminated. The employee emphatically announces, "I am invoking my Garrity Rights." What does this mean? Their invocation does not trigger their protection - the actions of the employer triggered Garrity protection before the employee said a word. Does their invocation now entitle them not to answer questions? Absolutely not. As previously stated, once use/derivative use immunity has been activated, the employee can no longer refuse to answer questions. So it is difficult to ascertain what the employee's invocation of their rights actually accomplishes. However, it must be acknowledged that an employee in an investigatory situation should endeavor to "cover all the bases" and make sure all parties are aware of the rights and obligations in place at the time; thus an invocation/affirmation of these rights certainly does no harm.

In an alternate scenario, the employee is called in for questioning, and upon entering the room, emphatically announces, "I am invoking my Garrity Rights." What does this mean? They have not been given any directives, nor have they been threatened with any penalty, real or implied. No compulsion has occurred yet. Therefore, Garrity Rights have not yet been triggered, notwithstanding the employee's invocation. Again, in a legal sense, the employee invocation accomplishes little; but it does no harm, as long as the employee fully understands it.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

What is use/derivative use immunity?

When people are given complete immunity from prosecution for a particular crime, it is known as "transactional" immunity.

In Garrity Rights cases, the immunity is not complete "transactional" immunity. In 1972's Kastigar v. United States, the Supreme Court held that immunity for compelled statements only applies to the use of the statements themselves, and to any evidence gained as a result of the protected statements. This is known as "use and derivative use" immunity, in which "use" is the use of the protected statements, and "derivative use" pertains to any evidence gained as a result of the protected statements. It is also known as "use plus fruits" immunity.

This means that the person in question can still be prosecuted for the offense under investigation, as long as the prosecution relies solely on evidence other than the protected statements and their fruits.

The result is that in many cases, what is known as a "Kastigar Hearing" takes place, in which the prosecution must demonstrate that its case rests solely on evidence other than the protected statements and their fruits.

Recently, this was significant in relation to the Nisour Square incident of September 16, 2007. On that day, Blackwater military contractors in Iraq killed 17 civilians in Baghdad's Nisour Square. In December 2008, the United States Department of Justice brought criminal charges against five of the contractors who had been involved, but the charges were dismissed in late 2009 because the prosecution had utilized evidence that was gained as a result of compelled statements.

It should be noted that full transactional immunity for compelled statements does apply in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as a result of the 1988 state supreme court decision in Carney v. City of Springfield.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

If I have Garrity protection, can I still take the Fifth and refuse to answer questions?

No. In "Uniformed Sanitation II," the court determined that once employees are protected by Garrity - meaning, their statements are protected by "use/derivative use" immunity - they are no longer able to refuse to answer questions. This is because once use/derivative use immunity is assured, the employee is no longer being required to give self-incriminating statements.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

I made statements after being told that if I refused to answer questions, I would face "discipline up to and including termination." Are my statements protected?

You are on potentially shaky ground, depending on where you live. In the states of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit (Maine, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire), the courts would likely find that your statements were voluntary because, while termination was a possibility, other less-severe sanctions were possibilities as well. See, for example, United States v. Indorato, Commonwealth v. Harvey, Singer v. Maine, Dwan v. City of Boston, and New Hampshire v. Litvin.

A number of other jurisdictions potentially subject to this narrow view include Illinois (People v. Bynum, 1987), Florida (United States v. Camacho, 1990), New Jersey (New Jersey v. Lacaillade, 1993), Idaho (State v. Connor, 1993), Minnesota (United States v. Najarian, 1996), Colorado (People v. Sapp, 1997, and Hopp & Flesch, LLC v. Backstreet, 2005) and Wisconsin (Wisconsin v. Brockdorf, 2006).

While many courts would find "discipline up to and including termination" coercive enough to trigger Garrity protection, it is also not hard to imagine other courts finding that coercion has not occurred if dismissal was possible but not definite. Obviously, then, the only way to be completely sure your statements are protected is to ensure that you are unequivocally subject to termination for refusal to answer. Otherwise, you gamble with the possibility that a court will deem your statements voluntary.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

What happened to Chief Garrity after Garrity v. New Jersey was decided?

Edward Garrity returned to his job as police chief of the township of Bellmawr, New Jersey. In 1969, just two years after the Garrity decision by the Supreme Court, he received the J. Edgar Hoover Award for Law Enforcement in New Jersey.

He retired from the Bellmawr police department in 1978, after serving as chief of police since 1951. Upon his retirement, he joined the Camden County Prosecutor's Office. He died in 2000.

It is also interesting to note that his father, James Garrity, was Bellmawr's chief of police from 1930-1949. So with just a two-year gap from 1949-1951, a member of the Garrity family was the township's police chief from 1930 to 1978.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Does Garrity protect false statements?

No. If an employee makes false statements under Garrity protection, they can be prosecuted for making false statements, and their statements can be used against them in that prosecution.

A number of courts have ruled that Garrity does not protect false statements. See McKinley v. City of Mansfield (6th Cir. 2005), U.S. v. Veal (11th Cir. 1998), FOP Lodge No. 5 v. City of Philadelphia (3rd Cir. 1988), U.S. v. Devitt (7th Cir. 1974), and U.S. ex. rel. Annunziato v. Deegan (2nd Cir. 1971).

The United States Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled that the Fifth Amendment does not shield perjured or false statements. See U.S. v. Wong (1977), U.S. v. Mandjuano (1976), and U.S. v. Knox (1969).

______________________________________________________________________________________

Does Garrity apply to drug tests, breathalyzer tests, etc?

No. Remember that Garrity Rights relate to the right not to be compelled to incriminate oneself. Courts have consistently found that this Fifth Amendment right applies only to statements, not to physical evidence. In Schmerber v. California, the United States Supreme Court stated that "the privilege is a bar against compelling 'communications' or 'testimony,' but that compulsion which makes a suspect or accused the source of 'real or physical evidence' does not violate it" (764). This doctrine extends as far back as 1910's Holt v. United States and even 1886's Boyd v. United States.

More recently, in the 2008 case Illinois v. Carey, a police officer who had been arrested for DUI argued that his breathalyzer results should be suppressed because he had been threatened with termination if he refused to take the test. The Illinois appellate court disagreed, saying that "it is well settled that the Fifth Amendment applies only to testimonial or communicative evidence and that it does not apply to physical evidence" (1139).

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

My question is not listed here. What can I do?

Feel free to contact me - I'll do my best to answer your question, or at least point you in the right direction.