Uniformed Sanitation Men Association v. Commissioner of Sanitation

("Uniformed Sanitation I")

392 U.S. 280 (1968)

Facts

In 1966, New York City began investigating allegations that employees of the Department of Sanitation were diverting disposal fees to themselves, defrauding the City of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Fifteen employees were summoned before the Commissioner of Sanitation, and each was informed that if they refused to answer on the basis of self-incrimination, they would be terminated in accordance with Section 1123 of the New York City Charter, which stated:

"If any councilman or other officer or employee of the city shall, after lawful notice or process, willfully refuse or fail to appear before any court or judge, any legislative committee, or any officer, board or body authorized to conduct any hearing or inquiry, or having appeared shall refuse to testify or to answer any question regarding the property, government or affairs of the city or of any county included within its territorial limits, or regarding the nomination, election, appointment or official conduct of any officer or employee of the city or of any such county, on the ground that his answer would tend to incriminate him, or shall refuse to waive immunity from prosecution on account of any such matter in relation to which he may be asked to testify upon any such hearing or inquiry, his term or tenure of office or employment shall terminate and such office or employment shall be vacant, and he shall not be eligible to election or appointment to any office or employment under the city or any agency."

Twelve of them asserted their constitutional privilege and refused to testify, and were terminated. Three answered questions and denied the accusations against them. These three were subsequently asked to sign waivers of immunity, and they refused. They were then terminated, in accordance with the City Charter.

The New York Court of Appeals held that the dismissal of the employees was constitutional.

Fifteen employees were summoned before the Commissioner of Sanitation, and each was informed that if they refused to answer on the basis of self-incrimination, they would be terminated in accordance with Section 1123 of the New York City Charter, which stated:

"If any councilman or other officer or employee of the city shall, after lawful notice or process, willfully refuse or fail to appear before any court or judge, any legislative committee, or any officer, board or body authorized to conduct any hearing or inquiry, or having appeared shall refuse to testify or to answer any question regarding the property, government or affairs of the city or of any county included within its territorial limits, or regarding the nomination, election, appointment or official conduct of any officer or employee of the city or of any such county, on the ground that his answer would tend to incriminate him, or shall refuse to waive immunity from prosecution on account of any such matter in relation to which he may be asked to testify upon any such hearing or inquiry, his term or tenure of office or employment shall terminate and such office or employment shall be vacant, and he shall not be eligible to election or appointment to any office or employment under the city or any agency."

Twelve of them asserted their constitutional privilege and refused to testify, and were terminated. Three answered questions and denied the accusations against them. These three were subsequently asked to sign waivers of immunity, and they refused. They were then terminated, in accordance with the City Charter.

The New York Court of Appeals held that the dismissal of the employees was constitutional.

Issue

Was it proper to terminate the sanitation employees for refusing to incriminate themselves?

Holding

Reversed. The termination of the employees was in violation of the U.S. Constitution.

Reasoning

- "Petitioners were not discharged merely for refusal to account for their conduct as employees of the city. They were dismissed for invoking and refusing to waive their constitutional right against self-incrimination" (283).

- "They were entitled to remain silent because it was clear that New York was seeking, not merely an accounting of their use or abuse of the public trust, but testimony from their own lips which, despite the constitutional prohibition, could be used to prosecute them criminally" (284).

- ". . . if New York had demanded that petitioners answer questions specifically, directly, and narrowly relating to the performance of their official duties on pain of dismissal from public employment without requiring the relinquishment of the benefits of constitutional privilege, and if they had refused to do so, this case would be entirely different" (284).

Commentary

In another pairing of related cases, the Supreme Court issued this decision on the same day as Gardner v. Broderick. Both decisions arise from Section 1123 of the New York City Charter.

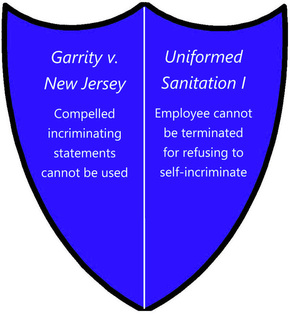

Garrity v. New Jersey and Uniformed Sanitation I can be viewed as a two-part package of rights. Garrity protects compelled statements from being used in a criminal proceeding, while Uniformed Sanitation I protects the employee from termination for refusing to self-incriminate. In other words, Garrity provides protections in regard to legal action (criminal proceedings), and Uniformed Sanitation I provides protections in regard to employer action (discipline). They are two sides of the same protective shield.

Garrity v. New Jersey and Uniformed Sanitation I can be viewed as a two-part package of rights. Garrity protects compelled statements from being used in a criminal proceeding, while Uniformed Sanitation I protects the employee from termination for refusing to self-incriminate. In other words, Garrity provides protections in regard to legal action (criminal proceedings), and Uniformed Sanitation I provides protections in regard to employer action (discipline). They are two sides of the same protective shield.